mothers

'dear mother'

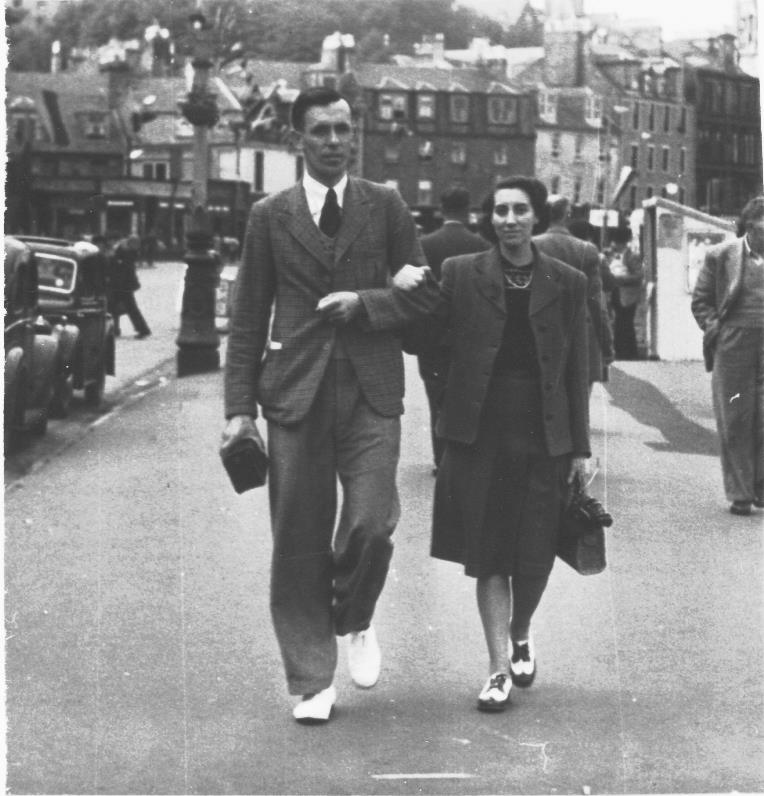

Ma with her brother Billy

Ma with her brother Billy

simultaneous writing to Kate 4th April 2019

Dear Ma,

Today you would be 107 years old – an unlikely event. I often think of how much you would approve of where we are living now – by the lake, in the country that is not so different from the Fens. And yet it is so different, and I am thinking of you particularly on Mothers’ Day this year. I am dressed in your old clothes and sitting in your wheelchair. I don’t remember how we changed from calling you ‘Mummy’ to ‘Ma’. I often wonder if you minded that – Peter and I decided call you Ma and from ‘Daddy’ to ‘Pa’. I think it must have been our feelings leaving from child to adult. You always called your own mother 'mother', I wonder if you ever called her ‘Mummy’? I don’t know why I am talking about this – perhaps I am feeling such a mixture of memories – when I recall our relationship through your life!

Anyway, now we are separated by your death thirteen yours ago, and today I’m imagining you are alive and as if you are beside me – can tell you many things that I would be able to tell you of joy and remorse, gratefulness and resentfulness that things bring to mind over our time – parent and child – parent and teenager – parent and adult daughter.

Sadly you were never destined to be Great Grandmother. How you would have loved Alani, Elvi, Sam and Merryn! They too would have loved you – bringing you unconditional love that you didn’t receive from me as adult. That’s where the remorse comes in; I found your constant needs when you were wheelchair-bound and living (only a short bike ride away in Carlisle) in a semi-sheltered flat. You were totally dependent, weren’t you, on someone helping you to the loo, bringing you a meal, helping you to get dressed each day and putting you to bed... You couldn’t even read any more since your stroke to pass the long hours.

But most of all you needed my visits – to give you a hug and just sitting with you. It pains me now you felt you needed to whisper ‘thank you’ to me for a kiss or put my arms around your fragile body. And you never lost your twinkling bright blue eyes that shone to see me, Nick, Cathy, Jon and Mary. You were in constant physical pain. And also in constant emotional anxious pain – about Pete particularly, but he at least gave you seemingly unconditional love. Of course I did visit you at least almost every other day, but I never displayed you any understanding, sympathy – did I? Your grandchildren loved you without resentment and when we were all together and took you out in the car – to the garden, a nearby park or a riverside accessible with your wheelchair – even out to a restaurant. We all enjoyed your own enjoyment. However, the worst of all my remorse is leaving you in hospital when I went away to Tonga with Jon, his 60th birthday gift to me. The worst for you was fear to die in hospital. And I left you there. Two weeks long – slipping away were you? Nick said you were waiting for me to get back – then you could let yourself die. Was that true?

Oh Ma – I never expressed any of this to you. It’s only now that I can understand, feel empathy with your condition. Despite I have had a stroke myself (I’m glad that you never knew) I can move, read, despite I have been so depended on Nick (you always loved him, and you would have liked to have seen more of him).

This letter so far has dwelt on the negative memories for me that are painful – my sorrow now, yes remorse. Now that you’re gone, I can’t tell you my sorrow; I wish I had been able to tell you. I suppose my love for you has never been unconditional since I left ‘home’. Now I want to ask you for your forgiveness, for all that I have caused you pain, for those things that I found so hard to do, to simply say ‘I love you’ in those years ago. I’m sure you would forgive me even now. Maybe I need to forgive myself. There are many good, happy memories of you, Ma. When I write again I hope we can start with ‘… and you remember that when we did…?’

Belatedly, I now want to send you my real heartfelt love,

Dianne

Dear Ma,

Today you would be 107 years old – an unlikely event. I often think of how much you would approve of where we are living now – by the lake, in the country that is not so different from the Fens. And yet it is so different, and I am thinking of you particularly on Mothers’ Day this year. I am dressed in your old clothes and sitting in your wheelchair. I don’t remember how we changed from calling you ‘Mummy’ to ‘Ma’. I often wonder if you minded that – Peter and I decided call you Ma and from ‘Daddy’ to ‘Pa’. I think it must have been our feelings leaving from child to adult. You always called your own mother 'mother', I wonder if you ever called her ‘Mummy’? I don’t know why I am talking about this – perhaps I am feeling such a mixture of memories – when I recall our relationship through your life!

Anyway, now we are separated by your death thirteen yours ago, and today I’m imagining you are alive and as if you are beside me – can tell you many things that I would be able to tell you of joy and remorse, gratefulness and resentfulness that things bring to mind over our time – parent and child – parent and teenager – parent and adult daughter.

Sadly you were never destined to be Great Grandmother. How you would have loved Alani, Elvi, Sam and Merryn! They too would have loved you – bringing you unconditional love that you didn’t receive from me as adult. That’s where the remorse comes in; I found your constant needs when you were wheelchair-bound and living (only a short bike ride away in Carlisle) in a semi-sheltered flat. You were totally dependent, weren’t you, on someone helping you to the loo, bringing you a meal, helping you to get dressed each day and putting you to bed... You couldn’t even read any more since your stroke to pass the long hours.

But most of all you needed my visits – to give you a hug and just sitting with you. It pains me now you felt you needed to whisper ‘thank you’ to me for a kiss or put my arms around your fragile body. And you never lost your twinkling bright blue eyes that shone to see me, Nick, Cathy, Jon and Mary. You were in constant physical pain. And also in constant emotional anxious pain – about Pete particularly, but he at least gave you seemingly unconditional love. Of course I did visit you at least almost every other day, but I never displayed you any understanding, sympathy – did I? Your grandchildren loved you without resentment and when we were all together and took you out in the car – to the garden, a nearby park or a riverside accessible with your wheelchair – even out to a restaurant. We all enjoyed your own enjoyment. However, the worst of all my remorse is leaving you in hospital when I went away to Tonga with Jon, his 60th birthday gift to me. The worst for you was fear to die in hospital. And I left you there. Two weeks long – slipping away were you? Nick said you were waiting for me to get back – then you could let yourself die. Was that true?

Oh Ma – I never expressed any of this to you. It’s only now that I can understand, feel empathy with your condition. Despite I have had a stroke myself (I’m glad that you never knew) I can move, read, despite I have been so depended on Nick (you always loved him, and you would have liked to have seen more of him).

This letter so far has dwelt on the negative memories for me that are painful – my sorrow now, yes remorse. Now that you’re gone, I can’t tell you my sorrow; I wish I had been able to tell you. I suppose my love for you has never been unconditional since I left ‘home’. Now I want to ask you for your forgiveness, for all that I have caused you pain, for those things that I found so hard to do, to simply say ‘I love you’ in those years ago. I’m sure you would forgive me even now. Maybe I need to forgive myself. There are many good, happy memories of you, Ma. When I write again I hope we can start with ‘… and you remember that when we did…?’

Belatedly, I now want to send you my real heartfelt love,

Dianne

Young Clarice

Young Clarice

simultaneous writing to Di 04 April 2019

Dear Mum, dear Clarice

I don’t think I ever addressed you by your given name – few did, since for years your shame about your poor northern background extended to your name; Clarice Cliff, Clarice Lispector were unknowns to you. I remember that one or two more pretentious acquaintances softened it to ‘Clarisse’ and there was a phase in my teens when I decided I would call you ‘Clare’. It didn’t last! But often, when I’m speaking or writing about you, I think of you as Clarice. And these days I regularly find myself doing both.

So. It’’s almost three years since you left us. I remember that evening in St George’s, 19th April, sitting with you, listening to you breathe. Jack had just left after staying through the previous night and a local minister had been rustled up by the staff to say a prayer. You weren’t conscious, not really. Still, as well as listening, I talked to you, goodness knows what about. I even sang to you. That would have surprised and tickled you if you heard – we were neither of us singers – and I like to think of you chuckling internally at this unlikely accompaniment to your departure. If I think back to my childhood, I remember your shy anxieties, your set face, your misery, your impatience, your temper, your moments of nastiness; as I grew older, your incomprehension as I veered off the path you had chosen for me, your disappointments in the kind of adult I became. I struggle to find memories of your laughter, even of you smiling, at least not until your last months. It seemed strange to me at your funeral that several people mentioned your sense of humour. I was left wondering if I ever knew you much at all.

Until you became ill, that is. I wasn’t sympathetic, not at first. All too easy to grumble to friends about the crazy parameters of ‘Nanaland’, your disappearances, your intractable habits, your routine dishonesties, your ‘accidents’, your denials. I recall so many instances when I was quick to criticise – an outburst of furious exasperation about the bits of toilet paper you stuffed inside your knickers instead of liners designed for the purpose (‘This is not the War..!’) or to correct – your insistence (obviously nonsense) that you had a ‘stand-up wash’ every morning, that you still did all your own housework. I wonder now why the truth mattered to me so much, when I was always ready to cover my tracks with a lie to avoid your censure.

Slowly, though, as you moved from one care home to another, fell more frequently, lost interest in your appearance and your personal hygiene (you who had been known for your elegance), became increasingly confused and detached, we seemed to find a new way to rub along together. Was it that I felt myself vulnerable, mirroring your decline with the deteriorations in my own health? Or were you losing the aspirations and affectations which had kept us apart all these years? When I saw you scooping marmalade out of its small plastic pot with your finger or heard in your speech those long-buried blunt vowels and dropped aitches of your Lancashire roots, it seemed as though I was seeing the ‘real’ Clarice for the first time. Contrary to those who sympathised with the cruelties of dementia – that it steals from us the person we have known and loved – in your case it seemed to free you from all that striving, all that pretending – and I found I liked the new (in fact, the old) Clarice better. We laughed a good deal together in your last weeks as I bumped you round the Botanics in a wheelchair or squabbled over the pottery class (never your favourite activity).

These days I think of you often, much more than I ever did when you were alive. This morning I remembered your struggles with the stairs in my tiny cottage in Cumbria, your reluctance to use the bath (not senseless obduracy as I thought at the time, of course, but the precarious nature of your balance, the fear of tumbling as you clambered in or out). You regularly pop into my mind as I stumble on a cracked pavement or experience the taste and texture of marmalade on my tongue. Often now, finding myself unable to engage with groups of people and retreating into embarrassed silence, I recall similar situations where your lack of involvement seemed to us simply laziness or, worse, bloody-mindedness.

Sometimes I wonder if we could have done better. I know that I lost sight of love during the final stages of your life, when you became an ongoing problem whose solution eluded us. Could we have kept you living in your ‘own place’ (the term was yours long after where you were living was not your place at all) for longer? Had we acted sooner, persuaded you to accept care at home, for instance, before you became ‘difficult’, would that have enabled you to hang on to your independence for a few more months? Or perhaps it goes back further than that: perhaps Baldock was a mistake. Should we have insisted on Cambridge, where it would have been so much easier to keep in touch and keep an eye on your decline? Jack would have seen more of you, I’m sure, if his visits didn’t necessitate a tiresome train journey. And you thought the world of Jack, able to lavish on him the unconditional love which we hope to find in our mothers and to find in ourselves to give to our children.

That night in St George’s, as your last breath proved to be your final one, I took a photo. Although only seconds after your death, the face was no longer recognisable as yours and it certainly wasn’t pretty. Jack was baffled: why on earth would I want a record of the moment when you became just another old person recently deceased? So I deleted it, choosing to keep instead the memory of you, still rather beautiful, at the garden party in the Hope, or under the cherry blossom in the Botanic Garden, in your woolly hat and good winter coat, smiling into the distance. Remembering Bill Viola’s video installation Nantes Tryptich, where the screen on the right documents his mother’s final week in her hospital bed, I wish now I’d kept the other too; as if, in that moment, we’d met properly for the first time, you as you really were, me as I am.

Dear Mum, dear Clarice

I don’t think I ever addressed you by your given name – few did, since for years your shame about your poor northern background extended to your name; Clarice Cliff, Clarice Lispector were unknowns to you. I remember that one or two more pretentious acquaintances softened it to ‘Clarisse’ and there was a phase in my teens when I decided I would call you ‘Clare’. It didn’t last! But often, when I’m speaking or writing about you, I think of you as Clarice. And these days I regularly find myself doing both.

So. It’’s almost three years since you left us. I remember that evening in St George’s, 19th April, sitting with you, listening to you breathe. Jack had just left after staying through the previous night and a local minister had been rustled up by the staff to say a prayer. You weren’t conscious, not really. Still, as well as listening, I talked to you, goodness knows what about. I even sang to you. That would have surprised and tickled you if you heard – we were neither of us singers – and I like to think of you chuckling internally at this unlikely accompaniment to your departure. If I think back to my childhood, I remember your shy anxieties, your set face, your misery, your impatience, your temper, your moments of nastiness; as I grew older, your incomprehension as I veered off the path you had chosen for me, your disappointments in the kind of adult I became. I struggle to find memories of your laughter, even of you smiling, at least not until your last months. It seemed strange to me at your funeral that several people mentioned your sense of humour. I was left wondering if I ever knew you much at all.

Until you became ill, that is. I wasn’t sympathetic, not at first. All too easy to grumble to friends about the crazy parameters of ‘Nanaland’, your disappearances, your intractable habits, your routine dishonesties, your ‘accidents’, your denials. I recall so many instances when I was quick to criticise – an outburst of furious exasperation about the bits of toilet paper you stuffed inside your knickers instead of liners designed for the purpose (‘This is not the War..!’) or to correct – your insistence (obviously nonsense) that you had a ‘stand-up wash’ every morning, that you still did all your own housework. I wonder now why the truth mattered to me so much, when I was always ready to cover my tracks with a lie to avoid your censure.

Slowly, though, as you moved from one care home to another, fell more frequently, lost interest in your appearance and your personal hygiene (you who had been known for your elegance), became increasingly confused and detached, we seemed to find a new way to rub along together. Was it that I felt myself vulnerable, mirroring your decline with the deteriorations in my own health? Or were you losing the aspirations and affectations which had kept us apart all these years? When I saw you scooping marmalade out of its small plastic pot with your finger or heard in your speech those long-buried blunt vowels and dropped aitches of your Lancashire roots, it seemed as though I was seeing the ‘real’ Clarice for the first time. Contrary to those who sympathised with the cruelties of dementia – that it steals from us the person we have known and loved – in your case it seemed to free you from all that striving, all that pretending – and I found I liked the new (in fact, the old) Clarice better. We laughed a good deal together in your last weeks as I bumped you round the Botanics in a wheelchair or squabbled over the pottery class (never your favourite activity).

These days I think of you often, much more than I ever did when you were alive. This morning I remembered your struggles with the stairs in my tiny cottage in Cumbria, your reluctance to use the bath (not senseless obduracy as I thought at the time, of course, but the precarious nature of your balance, the fear of tumbling as you clambered in or out). You regularly pop into my mind as I stumble on a cracked pavement or experience the taste and texture of marmalade on my tongue. Often now, finding myself unable to engage with groups of people and retreating into embarrassed silence, I recall similar situations where your lack of involvement seemed to us simply laziness or, worse, bloody-mindedness.

Sometimes I wonder if we could have done better. I know that I lost sight of love during the final stages of your life, when you became an ongoing problem whose solution eluded us. Could we have kept you living in your ‘own place’ (the term was yours long after where you were living was not your place at all) for longer? Had we acted sooner, persuaded you to accept care at home, for instance, before you became ‘difficult’, would that have enabled you to hang on to your independence for a few more months? Or perhaps it goes back further than that: perhaps Baldock was a mistake. Should we have insisted on Cambridge, where it would have been so much easier to keep in touch and keep an eye on your decline? Jack would have seen more of you, I’m sure, if his visits didn’t necessitate a tiresome train journey. And you thought the world of Jack, able to lavish on him the unconditional love which we hope to find in our mothers and to find in ourselves to give to our children.

That night in St George’s, as your last breath proved to be your final one, I took a photo. Although only seconds after your death, the face was no longer recognisable as yours and it certainly wasn’t pretty. Jack was baffled: why on earth would I want a record of the moment when you became just another old person recently deceased? So I deleted it, choosing to keep instead the memory of you, still rather beautiful, at the garden party in the Hope, or under the cherry blossom in the Botanic Garden, in your woolly hat and good winter coat, smiling into the distance. Remembering Bill Viola’s video installation Nantes Tryptich, where the screen on the right documents his mother’s final week in her hospital bed, I wish now I’d kept the other too; as if, in that moment, we’d met properly for the first time, you as you really were, me as I am.

inventory: items found in my mother's appartment after her move to The Hope

- Bottles of Harpic (11) (Today, returning from Boots, I notice that the number of unopened bottles of Simple eye makeup remover in my bathroom basket now amounts to three - oh dear!..!)

- Kitchen roll two-packs (7)

- 2lb bags of sugar (5)

- Packs of tomatoes, mouldy (3)

- Packs of 2 salmon fillets, long past their sell-by date (3)

- Grapefruit (13)

- Fairy liquid (5)

- Plastic carrier bags (22)

- Countless scraps of paper with notes, numbers, lists – one says ‘Mr Fairy’ and what might be a telephone number

- Photograph (black & white): a couple, sitting on a slatted garden bench outside what appears to be a pub or hotel, pose smiling for the camera. At least he is smiling, a model of relaxation, one arm extended along the seat back behind her, white shirt open at the collar, tie nowhere in sight. His hair, still mainly dark rather than grey, is receding slightly. He is in the foreground, of course, larger than life as always. She – my mum – is smaller, sharper, tucked behind him, almost smiling, but not quite. She looks quite poised, collected;; she could be bitchy behind that cool reserve; in a way she looks like a film star – or a bit part in a B movie. I don’t know where these unkind comments come from. I think I remember the occasion (c. 1993?) but they look impossibly young, and impossibly dated – more like 1960, perhaps earlier. Was I even born..?

- Crumpled bits of toilet tissue

- Empty face powders/hair spray

- A pale yellow plastic jug

- Almost finished bottles of nail varnish/shampoo

- Multi-packs of Imperial Leather soap (too many to count)

- Imperial Leather traces/soap scum (various)

- An empty silver pill box, hallmarked, hand-made, exterior much tarnished, with my initials KMC on the lid

- A knot of white hair, as if pulled from a hairbrush or comb

- A cut glass bowl of pot pourri, petals obscured under layers of dust

- A lingering cocktail of smells: soap, something sweet & cosmetic, vomit

- A bone china cup (Royal Doulton: Lexington), minus handle, containing an inch or so of scummy liquid

- On the floor behind the chest of drawers, a slew of turquoise-blue envelopes, printed with ‘St Mary’s Church Baldock’, some containing a £10 note, others empty

- A plastic bottle of carpet stain-remover, half-used

- An ancient leather wallet, inside, one church envelope containing coins, and a handful of loose change…

talking to ma mothers' day 2021

It's Mother's Day and as you are here I'll tell you some things I've been wishing I'd said this to you before.

It's just to say I'm sorry for all the pain I must have caused you as a teenager - all those hurtful things I must have said that must have been hurtful - you know what I'm talking about - I don't need to spell it out, this is simply to say today - I'm sorry - please forgive me. Much too late to be saying I love you. I NEVER CALLED YOU 'MOTHER' AS YOU WOULD LIKE TO HAVE BEEN CALLED. Now as it is Mother's Day, I would have liked to call you 'mother' as you always called your own mother - I feel sorry. I am really glad you are here - you like it - the place the house and the fact it's in France. I'd love to show you the pictures of Mary's children rejoicing in mother's day for her too! mother to daughter to mother - will her daughter be a mother? This is all I want to say today, only to add your always readiness to forgive - thank you. I want to hug you properly right now ...

It's Mother's Day and as you are here I'll tell you some things I've been wishing I'd said this to you before.

It's just to say I'm sorry for all the pain I must have caused you as a teenager - all those hurtful things I must have said that must have been hurtful - you know what I'm talking about - I don't need to spell it out, this is simply to say today - I'm sorry - please forgive me. Much too late to be saying I love you. I NEVER CALLED YOU 'MOTHER' AS YOU WOULD LIKE TO HAVE BEEN CALLED. Now as it is Mother's Day, I would have liked to call you 'mother' as you always called your own mother - I feel sorry. I am really glad you are here - you like it - the place the house and the fact it's in France. I'd love to show you the pictures of Mary's children rejoicing in mother's day for her too! mother to daughter to mother - will her daughter be a mother? This is all I want to say today, only to add your always readiness to forgive - thank you. I want to hug you properly right now ...

mothers day 14 march 2021

Dear Mum

A bit late in the day to be putting metaphorical pen to paper but, nudged by Di, there’s a sprig of rosemary for remembrance in the jug with the daffodils and the lamps are lit against the rain and the fading light (if you had your way, the blinds would all be firmly closed too - but I like to hang on to what is left of daylight until it’s quite gone). I guess that’s one of many differences between us - your love of cosy interiors, my desire to be out there and free - although age, what promises to be the tail end of lockdown and the steady progress of the Parkinson’s are beginning to blur the line so that I'm increasingly prone to ‘hibernating’ (your term) up here in my fourth floor eyrie.

Jack was here for lunch earlier. You would have enjoyed that although you might have been taken aback by his size. That wouldn’t have lasted, though - I was constantly surprised by your forgiving nature towards him - as if your first grandchild freed up the capacity for indulgence and unconditional love that didn’t come so easily to you as a parent. You would have enjoyed the halibut, too - I wonder if you remember one of our last visits to Fortnum’s basement, when we blanched simultaneously at the price tag - £17 plus if I remember it right - for a single piece of halibut! Characteristic of both of us, though, that neither had the courage to complain.

Would you like it here? I think the open-plan arrangement wouldn’t appeal to you and you might feel exposed, I imagine, with all the glass. But I think you would approve of the way even a part-ownership conveys a sort of success or status; as if somehow I have at last abandoned my naive idealistic notions and have ‘made it’ in the real world. Or am I putting words in your mouth here? Maybe you were waiting patiently all along and I simply took my time to fall into line?

A word about your ‘legacy’: now I’m speaking to you, I’m feeling rather uncertain - embarrassed, even - by my intention to sell the jewellery you left me. That must seem so ungrateful, especially as I know how hard you worked on the various pieces, most of which were designed for me and undoubtedly made with love. Maybe the weeks of hammering and soldering and engraving enabled you to channel the love for your wayward daughter, love that sometimes got lost along the way? If our positions were reversed now and you were contemplating selling words that I’d written for you, I would feel really hurt. It was Mel’s suggestion: that, rather than keep the pieces safe in a box, just taking them out now and again and replacing them, unworn, perhaps it would be better to trade them in and use the proceeds from the sale to buy - earrings, a ring maybe - that I would wear and, wearing, remember you? Now, I’m not so sure. I certainly intend to keep the gold earrings with the sapphires that Poppa brought back from India. In fact, I wear them most days and will never part with them. And I have one of your candlesticks and Jack’s napkin ring - sadly I can’t find mine anywhere. The rest, though - what do you think? The Crown Derby brooch, the cameo, the pin, even the lovely rings - well, the rings won’t go anywhere near my bony old fingers now. And I do prefer silver.. . I have a sort of alternative idea for the peridot ring - more later on this.

For now, afternoon has turned into evening and I think that’s about it for today. There may be more tomorrow!

With love

Kate xx

15 march

Hello again

The peridot: a local jeweller whose work I admire and who has agreed to look at your jewellery collection includes in her designs a ring comprising a silver band with a gold-mounted peridot. I am thinking that might be a way of incorporating your work into a new piece. At any rate, I really like the idea of enjoying wearing pieces which connect me to you so I’m trusting to fate that you won’t be overly offended by my actions.

On the subject of offence, I’ve wondered often how you felt about being parked in care. Despite your insistence that when you were ‘old and decrepit’ we should put you in a home, you were evidently outraged at times by the loss of your freedom and I’ve often felt - still feel - that we could, should have done better for you. I certainly don’t want to find myself in a similar situation though I wonder how much choice any of us has as life draws to a close. I’ve often wondered, too, how far you were aware in those last days that your life was ending. Did you know that Jack watched by your bed through your penultimate night or that I was there as you drew your final breaths, chatting to you, even singing - the Brahms lullaby, the song I used to sing Jack to sleep?

We’ll never know. I do know that you are remembered with affection by many who knew you and with a surprised kind of enduring love by those closest to you - the last is certainly true for me. As Poppa’s birthday approaches, I’d like to think that you have found each other in some parallel universe, that you are at peace and that you forgive us our many shortcomings.

With love

Dear Mum

A bit late in the day to be putting metaphorical pen to paper but, nudged by Di, there’s a sprig of rosemary for remembrance in the jug with the daffodils and the lamps are lit against the rain and the fading light (if you had your way, the blinds would all be firmly closed too - but I like to hang on to what is left of daylight until it’s quite gone). I guess that’s one of many differences between us - your love of cosy interiors, my desire to be out there and free - although age, what promises to be the tail end of lockdown and the steady progress of the Parkinson’s are beginning to blur the line so that I'm increasingly prone to ‘hibernating’ (your term) up here in my fourth floor eyrie.

Jack was here for lunch earlier. You would have enjoyed that although you might have been taken aback by his size. That wouldn’t have lasted, though - I was constantly surprised by your forgiving nature towards him - as if your first grandchild freed up the capacity for indulgence and unconditional love that didn’t come so easily to you as a parent. You would have enjoyed the halibut, too - I wonder if you remember one of our last visits to Fortnum’s basement, when we blanched simultaneously at the price tag - £17 plus if I remember it right - for a single piece of halibut! Characteristic of both of us, though, that neither had the courage to complain.

Would you like it here? I think the open-plan arrangement wouldn’t appeal to you and you might feel exposed, I imagine, with all the glass. But I think you would approve of the way even a part-ownership conveys a sort of success or status; as if somehow I have at last abandoned my naive idealistic notions and have ‘made it’ in the real world. Or am I putting words in your mouth here? Maybe you were waiting patiently all along and I simply took my time to fall into line?

A word about your ‘legacy’: now I’m speaking to you, I’m feeling rather uncertain - embarrassed, even - by my intention to sell the jewellery you left me. That must seem so ungrateful, especially as I know how hard you worked on the various pieces, most of which were designed for me and undoubtedly made with love. Maybe the weeks of hammering and soldering and engraving enabled you to channel the love for your wayward daughter, love that sometimes got lost along the way? If our positions were reversed now and you were contemplating selling words that I’d written for you, I would feel really hurt. It was Mel’s suggestion: that, rather than keep the pieces safe in a box, just taking them out now and again and replacing them, unworn, perhaps it would be better to trade them in and use the proceeds from the sale to buy - earrings, a ring maybe - that I would wear and, wearing, remember you? Now, I’m not so sure. I certainly intend to keep the gold earrings with the sapphires that Poppa brought back from India. In fact, I wear them most days and will never part with them. And I have one of your candlesticks and Jack’s napkin ring - sadly I can’t find mine anywhere. The rest, though - what do you think? The Crown Derby brooch, the cameo, the pin, even the lovely rings - well, the rings won’t go anywhere near my bony old fingers now. And I do prefer silver.. . I have a sort of alternative idea for the peridot ring - more later on this.

For now, afternoon has turned into evening and I think that’s about it for today. There may be more tomorrow!

With love

Kate xx

15 march

Hello again

The peridot: a local jeweller whose work I admire and who has agreed to look at your jewellery collection includes in her designs a ring comprising a silver band with a gold-mounted peridot. I am thinking that might be a way of incorporating your work into a new piece. At any rate, I really like the idea of enjoying wearing pieces which connect me to you so I’m trusting to fate that you won’t be overly offended by my actions.

On the subject of offence, I’ve wondered often how you felt about being parked in care. Despite your insistence that when you were ‘old and decrepit’ we should put you in a home, you were evidently outraged at times by the loss of your freedom and I’ve often felt - still feel - that we could, should have done better for you. I certainly don’t want to find myself in a similar situation though I wonder how much choice any of us has as life draws to a close. I’ve often wondered, too, how far you were aware in those last days that your life was ending. Did you know that Jack watched by your bed through your penultimate night or that I was there as you drew your final breaths, chatting to you, even singing - the Brahms lullaby, the song I used to sing Jack to sleep?

We’ll never know. I do know that you are remembered with affection by many who knew you and with a surprised kind of enduring love by those closest to you - the last is certainly true for me. As Poppa’s birthday approaches, I’d like to think that you have found each other in some parallel universe, that you are at peace and that you forgive us our many shortcomings.

With love