maps

|

From 'A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 100 OBJECTS' BBC Radio 4: Episode 88 North American Buckskin Map This copy of a map records the sale of a piece of land and reflects the European understanding of maps as evidence of power and control, in contrast with the Native American 'deep and spiritual connection to the land' (Neil MacGregor) For tribes such as the Piankashaw, “…one could not any more own the land than one could own the air above the land or the rain that fell on it…” (David Edmunds Professor of American History at the University of Texas) |

di (2000): territories

"I wanted to make more process-driven work based on the concept of personal relatedness to place. I began to make marks in places that were meaningful to me – a marking of place without leaving visible trace.

To do this, I urinated on the ground of six different locations; three in Cumbria where I lived, two in Devon where I had holidayed throughout my life, and two in Scotland where I had camped each May while living in Carlisle.

Territories map 1, therefore, depicts these locations. I used Photoshop to create a ‘map’ of my own from scanned 1:50,000 Ordnance Survey maps. The exact spots are recorded through a stencil mark on the resulting map. The front cover of this created map is made up of the photographs of these spots. The back cover of the map is a ‘key’ – a list of words describing the type of location where the marks were made.

This work related to my drawing practice – mark-making, printing, imprinting – and also references the ‘journey’ that continued to be important for me."

"I wanted to make more process-driven work based on the concept of personal relatedness to place. I began to make marks in places that were meaningful to me – a marking of place without leaving visible trace.

To do this, I urinated on the ground of six different locations; three in Cumbria where I lived, two in Devon where I had holidayed throughout my life, and two in Scotland where I had camped each May while living in Carlisle.

Territories map 1, therefore, depicts these locations. I used Photoshop to create a ‘map’ of my own from scanned 1:50,000 Ordnance Survey maps. The exact spots are recorded through a stencil mark on the resulting map. The front cover of this created map is made up of the photographs of these spots. The back cover of the map is a ‘key’ – a list of words describing the type of location where the marks were made.

This work related to my drawing practice – mark-making, printing, imprinting – and also references the ‘journey’ that continued to be important for me."

di: the woods memory map

Beginning to walk alone again after I had had a stroke, I explored the little woods near to where we live now.

When I passed particular spots on the way, I began to name them as fanciful places such as – “witches’ coven”, “wizards’ well” or other names serving as mark-ways such as “leafy lane” or “bird song corner”.

Back home, inspired by the Samuel Coleridge Lakes Notebook 1802, I tried to remember my route and write it on paper.

After several unsuccessful attempts – I didn’t expect it to be so hard to visualize the route on paper and connect it to my hand! So after more walking the route from memory, I came up with the resulting ‘map’ on paper.

My grandchildren used it to find their way to follow my route in the woods when they visited.

on maps and mapping: kate

I hated geography at school and had no interest in maps. Despite a teenage conviction that one day I would see India, I wasn’t even much interested in the world beyond my window and made little use of the free train travel across Europe I earned for being a railwayman’s daughter. So it seems strange that by my mid-thirties I was desperate to get away and ironic that at the age of 37 I found myself in a classroom in Mexico City teaching international students from the same British Geography textbook I was burdened with as a child. I had a wall map of the country pinned to a cupboard door in the small house I rented on the western edge of the city. The map provided inspiration for many weekends away in the beat-up old ‘Bocho’ that belonged to my two young Canadian friends and it (map not car) was later transferred to a wall in our house in Cumbria, keeping alive the promise that I’d return to Mexico one day. I didn’t, though the map has survived, yellowing and tattered, traces of blu-tack on the corners. I unfold it gingerly, some of its sections cracking apart along the folds. I spread it out on the table and peer at the names, searching for the familiar, retracing my footprint as memories leap up at me: the hit of the exhaust-heavy air when you arrive, frosty January wakings, the tops of the volcanoes against the blue on the rare clear morning, the steamy heat of a jungle dawn, the bite of salsa on the tongue before the rush of cold beer, tamales and nopales and huitlacoche, faces and voices, the person I was, the tears I cried, the futures I imagined; a tangible link to a world that I once claimed as mine.

Like the maps of our childhood territory – Middle Earth and Narnia, the Hundred Acre Wood and the riverbank – my Mexican map represents both adventure and security. Like the maps in Coleridge’s notebooks, it’s a record, a memento of personal wanderings. Other maps have become souvenirs, too: the one that marks all the milongas in Buenos Aires, so well-used it’s on the point of disintegrating or the hundred-plus pages of maps that accompany the bus timetable for the same city, confusingly following the usual orientation of north at the top whilst most maps in Argentina point south. I was intrigued to stumble online upon a 1950s CIA surveillance map of a village I’d visited in Bulgaria, with details of each household and workplace with an assessment of their security risk. An entirely other revisioning of the map is a memorial to my friend and poet Pauline Radley which folds out like an OS map but is composed of poems about trees, with pen and ink drawings. Or there is the radical vision of Iain Sinclair, walking a ‘crude V’ in east London, ‘recording and retrieving the messages on walls, lampposts, door jambs… Railway to pub to hospital: trace the line on the map… the born-again flaneur is a stubborn creature, less interested in texture and fabric, eavesdropping on philosophical conversation pieces, than in noticing everything.’[1] Some maps take on a talismanic quality: my pocket-size A-Z still comes with me when I make it to London though who needs it when Google Maps is so comprehensive? In times when venturing far is difficult, a map is a resource for the armchair traveller, an invitation to ‘boldly go’, to head ‘to infinity and beyond’, at least in the imagination. Like a musical score, it can be a route to beauty, or a work of art in itself, such as Robert Smithson’s installation ‘Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis)’. Books about journeys are often prefaced with a map – in Patagonia, A Time of Gifts, Passage to Juneau; in others (especially fiction – Robinson Crusoe, Heart of Darkness, Huckleberry Finn) the map is implied. Maps may offer clues – as in ‘x marks the spot’ to buried treasure – though often there is a puzzle to solve, if not a deliberate attempt to send the treasure-seeker off on a false trail. There are maps for walkers that accrue in their crumpled weather-worn state the particular memory of a wind-swept fell-top, for example, along with the person who shared the day, maps for cyclists and farmers and tourists, maps of the cosmos and astrological charts. There are many alternatives to what has become the traditional two-dimensional paper projection, from song lines and ley lines to Greenland’s maps traditionally carved in stone or bone so that the terrain or coastline can be traced with the fingers inside a sealskin mitt in extreme temperatures. In The Library of Ice, Nancy Campbell describes the way sled trails & skate traces & footsteps in the snow become maps or, of Antarctic explorers: ‘the snow that they stepped on, compressed by the weight of the body, would remain fixed in place as the lighter, unmarked snow around them blew away. These pillars of ice were visible from far away long after the explorer had passed on.’

The concept of life as a journey has become all too familiar: from the wanderings of Ulysses or his latter-day alter ego Leopold Bloom to the enforced real-life migration of those forced to flee danger or deprivation, it is hard not to see ourselves as travellers in search of some goal. The poet Cavafy advises

hope your road is a long one

full of adventure, full of discovery[2]

Mary Oliver sees us as part of a world in motion:

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again…[3]

As we embarked on our project, we saw the correspondences in our timelines and attempted to map our memories following the paths of early cartographers, drawing our worlds according to what we knew, with ourselves at the centre. We altered coastlines and contours to reflect our own experiences, always in search of that elusive representation of our separate paths, occasionally touching, sometimes crossing, sometimes running alongside each other before veering apart again. My initial vision of a Perspex block continues to elude us but the search remains infinitely absorbing.

[1] Iain Sinclair: Lights Out for the Territory

[2] CP Cavafy: ‘Ithaca’

[3] Mary Oliver: ‘Wild Geese’

I hated geography at school and had no interest in maps. Despite a teenage conviction that one day I would see India, I wasn’t even much interested in the world beyond my window and made little use of the free train travel across Europe I earned for being a railwayman’s daughter. So it seems strange that by my mid-thirties I was desperate to get away and ironic that at the age of 37 I found myself in a classroom in Mexico City teaching international students from the same British Geography textbook I was burdened with as a child. I had a wall map of the country pinned to a cupboard door in the small house I rented on the western edge of the city. The map provided inspiration for many weekends away in the beat-up old ‘Bocho’ that belonged to my two young Canadian friends and it (map not car) was later transferred to a wall in our house in Cumbria, keeping alive the promise that I’d return to Mexico one day. I didn’t, though the map has survived, yellowing and tattered, traces of blu-tack on the corners. I unfold it gingerly, some of its sections cracking apart along the folds. I spread it out on the table and peer at the names, searching for the familiar, retracing my footprint as memories leap up at me: the hit of the exhaust-heavy air when you arrive, frosty January wakings, the tops of the volcanoes against the blue on the rare clear morning, the steamy heat of a jungle dawn, the bite of salsa on the tongue before the rush of cold beer, tamales and nopales and huitlacoche, faces and voices, the person I was, the tears I cried, the futures I imagined; a tangible link to a world that I once claimed as mine.

Like the maps of our childhood territory – Middle Earth and Narnia, the Hundred Acre Wood and the riverbank – my Mexican map represents both adventure and security. Like the maps in Coleridge’s notebooks, it’s a record, a memento of personal wanderings. Other maps have become souvenirs, too: the one that marks all the milongas in Buenos Aires, so well-used it’s on the point of disintegrating or the hundred-plus pages of maps that accompany the bus timetable for the same city, confusingly following the usual orientation of north at the top whilst most maps in Argentina point south. I was intrigued to stumble online upon a 1950s CIA surveillance map of a village I’d visited in Bulgaria, with details of each household and workplace with an assessment of their security risk. An entirely other revisioning of the map is a memorial to my friend and poet Pauline Radley which folds out like an OS map but is composed of poems about trees, with pen and ink drawings. Or there is the radical vision of Iain Sinclair, walking a ‘crude V’ in east London, ‘recording and retrieving the messages on walls, lampposts, door jambs… Railway to pub to hospital: trace the line on the map… the born-again flaneur is a stubborn creature, less interested in texture and fabric, eavesdropping on philosophical conversation pieces, than in noticing everything.’[1] Some maps take on a talismanic quality: my pocket-size A-Z still comes with me when I make it to London though who needs it when Google Maps is so comprehensive? In times when venturing far is difficult, a map is a resource for the armchair traveller, an invitation to ‘boldly go’, to head ‘to infinity and beyond’, at least in the imagination. Like a musical score, it can be a route to beauty, or a work of art in itself, such as Robert Smithson’s installation ‘Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis)’. Books about journeys are often prefaced with a map – in Patagonia, A Time of Gifts, Passage to Juneau; in others (especially fiction – Robinson Crusoe, Heart of Darkness, Huckleberry Finn) the map is implied. Maps may offer clues – as in ‘x marks the spot’ to buried treasure – though often there is a puzzle to solve, if not a deliberate attempt to send the treasure-seeker off on a false trail. There are maps for walkers that accrue in their crumpled weather-worn state the particular memory of a wind-swept fell-top, for example, along with the person who shared the day, maps for cyclists and farmers and tourists, maps of the cosmos and astrological charts. There are many alternatives to what has become the traditional two-dimensional paper projection, from song lines and ley lines to Greenland’s maps traditionally carved in stone or bone so that the terrain or coastline can be traced with the fingers inside a sealskin mitt in extreme temperatures. In The Library of Ice, Nancy Campbell describes the way sled trails & skate traces & footsteps in the snow become maps or, of Antarctic explorers: ‘the snow that they stepped on, compressed by the weight of the body, would remain fixed in place as the lighter, unmarked snow around them blew away. These pillars of ice were visible from far away long after the explorer had passed on.’

The concept of life as a journey has become all too familiar: from the wanderings of Ulysses or his latter-day alter ego Leopold Bloom to the enforced real-life migration of those forced to flee danger or deprivation, it is hard not to see ourselves as travellers in search of some goal. The poet Cavafy advises

hope your road is a long one

full of adventure, full of discovery[2]

Mary Oliver sees us as part of a world in motion:

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again…[3]

As we embarked on our project, we saw the correspondences in our timelines and attempted to map our memories following the paths of early cartographers, drawing our worlds according to what we knew, with ourselves at the centre. We altered coastlines and contours to reflect our own experiences, always in search of that elusive representation of our separate paths, occasionally touching, sometimes crossing, sometimes running alongside each other before veering apart again. My initial vision of a Perspex block continues to elude us but the search remains infinitely absorbing.

[1] Iain Sinclair: Lights Out for the Territory

[2] CP Cavafy: ‘Ithaca’

[3] Mary Oliver: ‘Wild Geese’

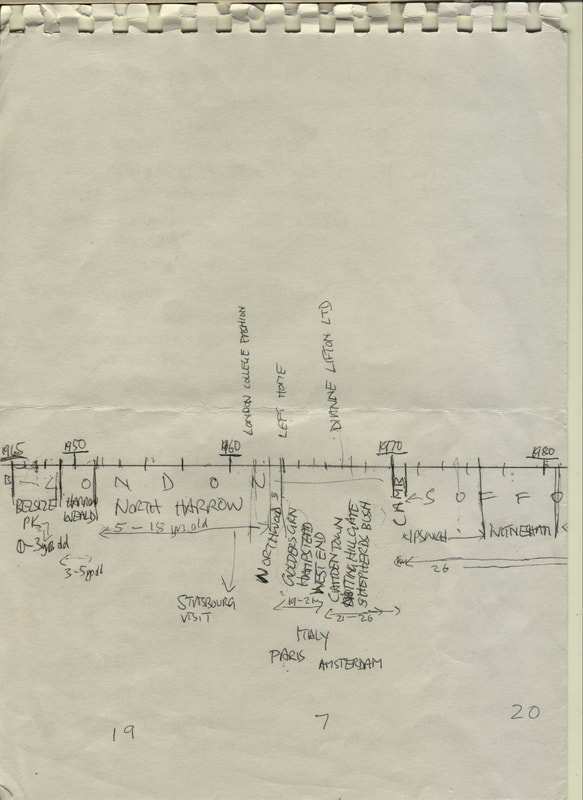

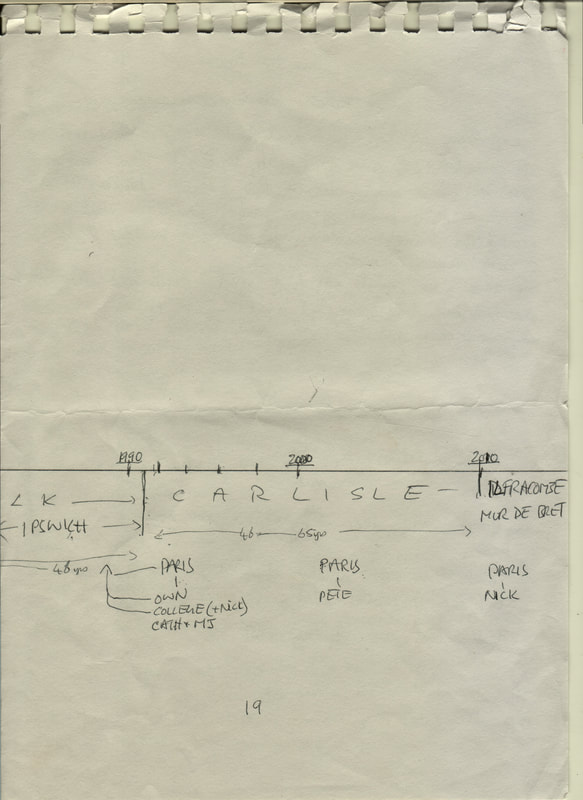

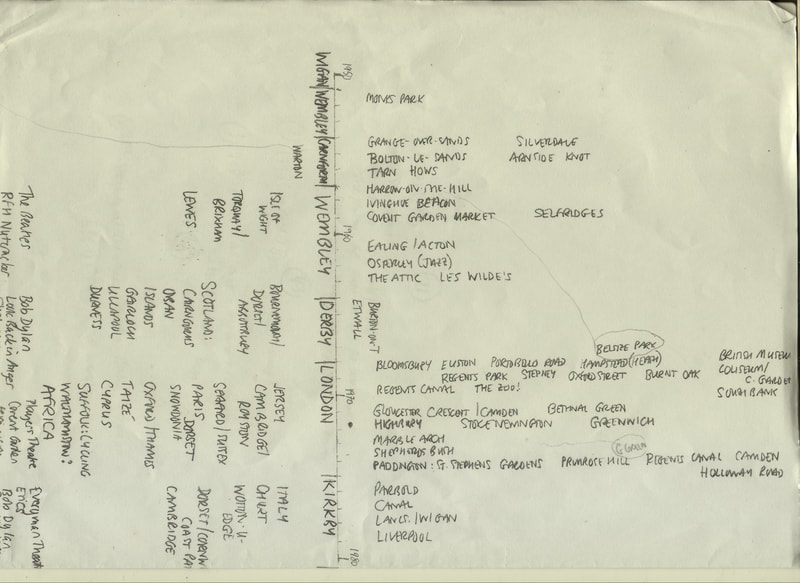

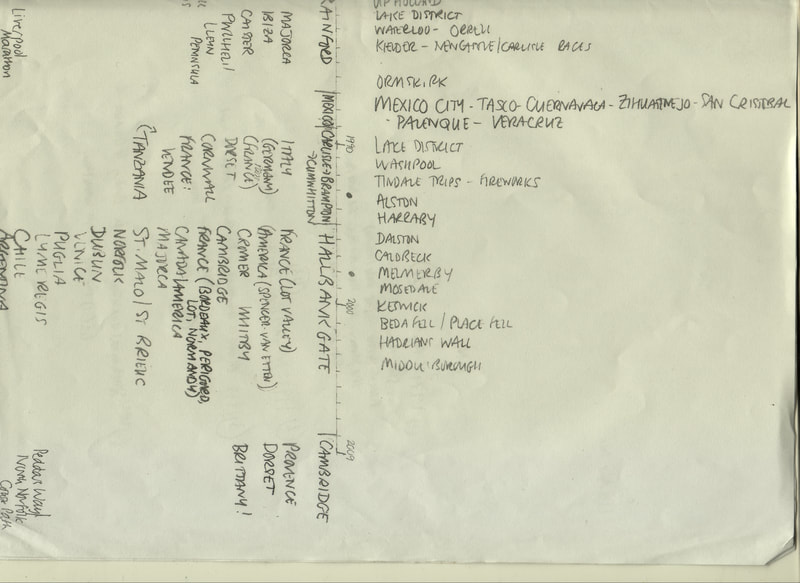

our timelines

rethinking geographies

responding to others' maps

(from Mapping it Out, An Alternative Atlas of Contemporary Cartographies, edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2014)

ARTIST TEHCHING HSIEH New York Manhattan (pages 74-75)

I immediately warm to this map, mainly because it is a necessarily within part of the creation of a performance. This itself is a wider large year-long performances. Maybe I am cheating a bit because I am familiar with Tehching Hseih’ work and like a lot the conception of his work. All his work is in a way in process. For this performance he has recorded or planned (probably) a journey by drawing the route and notes onto an already existing map. The map is now changed by his drawing. It isn’t made as a finished art image, but as directions for him to follow. It seems to me that it is strongly related to how we work, Mapping Memory.

ARTIST TEHCHING HSIEH New York Manhattan (pages 74-75)

I immediately warm to this map, mainly because it is a necessarily within part of the creation of a performance. This itself is a wider large year-long performances. Maybe I am cheating a bit because I am familiar with Tehching Hseih’ work and like a lot the conception of his work. All his work is in a way in process. For this performance he has recorded or planned (probably) a journey by drawing the route and notes onto an already existing map. The map is now changed by his drawing. It isn’t made as a finished art image, but as directions for him to follow. It seems to me that it is strongly related to how we work, Mapping Memory.

ARTIST TEHCHING HSIEH New York Manhattan (PAGES 74-75)

Mark 2

This map doesn’t make a lot of sense as an art image without knowing the context – the necessary preparation of a performance which is in itself one of the artist’s series of one year-long actions. These series of performances/actions are ‘Life Works’ dealing with the concept of ‘time’ by repeating an action each day throughout a year. The section of the map of New York has been drawn on, therefore creating a new image by the artist. This therefore is an expression as a process towards an action. I find many connections in this to our Mapping Memory work: using actual maps; concerning with time; creating objects (not as performances) to express our preoccupations (the abstract idea of ‘other to the other’); the importance of understanding as the actual work as process. I like that this stand-alone image of Hsieh’s leads to asking questions and that is not one of the important values of art?

Mark 2

This map doesn’t make a lot of sense as an art image without knowing the context – the necessary preparation of a performance which is in itself one of the artist’s series of one year-long actions. These series of performances/actions are ‘Life Works’ dealing with the concept of ‘time’ by repeating an action each day throughout a year. The section of the map of New York has been drawn on, therefore creating a new image by the artist. This therefore is an expression as a process towards an action. I find many connections in this to our Mapping Memory work: using actual maps; concerning with time; creating objects (not as performances) to express our preoccupations (the abstract idea of ‘other to the other’); the importance of understanding as the actual work as process. I like that this stand-alone image of Hsieh’s leads to asking questions and that is not one of the important values of art?

ARTIST DAVE MCKEAN

A Map of the Human Heart (page 134)

I couldn’t resist this! The artist’s note references his contributions to ‘psychogeographer and national treasure Iain Sinclair’s love letter to the M25 motorway, London Orbital’. I have just finished reading Sinclair’s Lights Out for the Territory & am so looking forward to LO. His writing is extraordinary – full of energy and feeling, often funny or challenging, with an amazing breadth of knowledge which leaves me breathless. His work is fuelled by walking – or ‘stalking’ his preferred term – and an attempt I suppose to record the beating heart of the city, what lies beneath the surface in subcultures and out-of-the-way neighbourhoods. He plunders history, too, and film/music/ photography, an immensely rich other world…

And the map? A modest outline map of the city overlaid with a stylised black outline of the heart. Red blocks of colour at the centre feed out into narrowing lines and also dotted lines – are these veins and arteries, or a representation of the orbital motorway, or both? Resonances: the original title of my first (Argentinian) novel was ‘A Human Heart’, from my sense that our hearts are capable of apparently limitless evil, and also limitless goodness. Also London: so much of our own memory project is rooted in and around the city. More generally, our sense of place: in our work, are we trying to get to the bottom of what it is about a particular place which holds us, which makes us value it and want to return, to re-establish our connection with it..?

Looking at another map

I have to say I’ve had a problem choose one so I’m going to bend the rules to mention four maps and then write about one in a little more detail – see how far I go!

1. ARTIST JONAS MEKAS A Map of 1960’s New York from Memory (pages 14-15)

The artist has lived in 1960’s and has created an image of the places where he as worked, lived, visited etc from his memory…

I think this idea is quite inspiring as a way we could talk to make similar maps – overlay ours made in transparent paper …?

2. ARTIST ADAM CHODZKO Night Shift: The Wrong Map (pages 22-23)

Map made alternative route by tracking the journeys of animals

3. ARTIST PHILIP HUGHES Ingleborough 9pages 50-51)

Creating beautiful images based on scientific research

4. ARTIST JOEL GOLD Object Relational … Brain (page 58)

Inspired to make a map of my own brain based on emotions over relationships

So back to number 3.

I think this is the most different personal connection to the others and the images that have created sensitive little paintings(?) that would not immediately connect to maps, nevertheless an ordinance map has been used in the initial process.

At this point I am not making sense and I’m having a lot of difficulty to find the words I need – there are many things I would like to write a lot of this map. I think I have tripped myself up by not talking just one of them at the bginning beginning… Maybe I can return to this at some point.

Ridiculously this far I’ve at it nearly for one hour!!! Frustrating. However, I like the process – I’m not well yet, even though sometimes start a process as if I am!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Better stop – give the brain a break...

***

What I wanted to say…

Walking - beneath the Cumbrian Fells, the Scottish mountain sides – where I was touching the surfaces, looking as much at the grounds as the formations around me and the distant views, the stream cutting its way between small crevices in the rock moved me to write little ‘poems’ (not shown to others). Walking alone then sitting down for a rest, I wanted to mark these places in some way – claiming for myself a share of a little bit of ground – to be part of this place in the time always. If, in the future, there ways to ‘see’ footprints pre-amongst the grasslands, would mine be detected amongst the animals, birds, insects that were their territories? Of course not. However, my work, Territories, where I left my marks by urinating there, I photographed the spots and marked them on the various locations on OS maps. I consolidated these different places by creating an-other map.

Hughes’ Ingleborough art has been inspired by the ground beneath the surrounding hillsides.

Using geologic information and the OS maps, has gone further to create a quite different art form – small water colours to connect the three peaks. I was attracted to these delicate images – a bit likes explicit drawings of recordings of plants made by explorers in the past. These paintings are not in any way visual connections to maps.

I have to say I’ve had a problem choose one so I’m going to bend the rules to mention four maps and then write about one in a little more detail – see how far I go!

1. ARTIST JONAS MEKAS A Map of 1960’s New York from Memory (pages 14-15)

The artist has lived in 1960’s and has created an image of the places where he as worked, lived, visited etc from his memory…

I think this idea is quite inspiring as a way we could talk to make similar maps – overlay ours made in transparent paper …?

2. ARTIST ADAM CHODZKO Night Shift: The Wrong Map (pages 22-23)

Map made alternative route by tracking the journeys of animals

3. ARTIST PHILIP HUGHES Ingleborough 9pages 50-51)

Creating beautiful images based on scientific research

4. ARTIST JOEL GOLD Object Relational … Brain (page 58)

Inspired to make a map of my own brain based on emotions over relationships

So back to number 3.

I think this is the most different personal connection to the others and the images that have created sensitive little paintings(?) that would not immediately connect to maps, nevertheless an ordinance map has been used in the initial process.

At this point I am not making sense and I’m having a lot of difficulty to find the words I need – there are many things I would like to write a lot of this map. I think I have tripped myself up by not talking just one of them at the bginning beginning… Maybe I can return to this at some point.

Ridiculously this far I’ve at it nearly for one hour!!! Frustrating. However, I like the process – I’m not well yet, even though sometimes start a process as if I am!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Better stop – give the brain a break...

***

What I wanted to say…

Walking - beneath the Cumbrian Fells, the Scottish mountain sides – where I was touching the surfaces, looking as much at the grounds as the formations around me and the distant views, the stream cutting its way between small crevices in the rock moved me to write little ‘poems’ (not shown to others). Walking alone then sitting down for a rest, I wanted to mark these places in some way – claiming for myself a share of a little bit of ground – to be part of this place in the time always. If, in the future, there ways to ‘see’ footprints pre-amongst the grasslands, would mine be detected amongst the animals, birds, insects that were their territories? Of course not. However, my work, Territories, where I left my marks by urinating there, I photographed the spots and marked them on the various locations on OS maps. I consolidated these different places by creating an-other map.

Hughes’ Ingleborough art has been inspired by the ground beneath the surrounding hillsides.

Using geologic information and the OS maps, has gone further to create a quite different art form – small water colours to connect the three peaks. I was attracted to these delicate images – a bit likes explicit drawings of recordings of plants made by explorers in the past. These paintings are not in any way visual connections to maps.